Black Hawk

The Black Hawk War of 1832

This was not a decision he made casually. He had assurances from some of his friends-Wabokieshiek or "the Winnebago Prophet" whose tribe still resided in Illinois offered to accept Black Hawk and his followers into his village. Neapope, a Sauk Chief, promised his support,and visited British General Gaines expecting to get military support.

Black Hawk brought with him somewhere around two thousand followers--maybe six hundred of them warriors, the rest women, children, and old men. The majority of the Sauk tribe stayed on the western side of the river with Keokuk, however.

On April 3, Black Hawk and his band crossed the Mississippi River near the mouth of the Des Moines. They proceded up the Rock River towards Saukenuk. While on the move they beat on their war drums and did war dances. They were loud. They were prepared for conflict, but that does not mean they wanted an all-out war. The intent was to stay in their home village for the summer, plant corn, beans, and pumpkins.

But the situation was rapidly changing. Black Hawk found settlers and troops near Saukenuk so continued up the Rock River to the Prophet's village. When he did not find the support there that he had expected, he continued moving up the Rock River. By late April and early May, a band of militia had been called up by Governor Reynolds (governor of Illinois). By May 10, U.S. troops were following Black Hawk's Band up the river. On May 13, Black Hawk found that he no longer could avoid the militia. He sent a party of three warriors, under a white flag, to negotiate a surrender. He also sent a party of five to watch the negotiations.

What followed was known to history as "The Battle of Stillman's Run," the first of a series of encounters that became known as The Black Hawk War.

While the three were negotiating with the undisciplined and nervous militia, someone spotted the observers. A number of the militia took off after them and in the confusion, the observers returned fire--two were killed, and one of the indian negotiators was also killed. The remainder of the warriors made it back to Black Hawk's camp.

Black Hawk took about forty warriors--the rest of his party being a considerable distance away, and organized a mounted counterattack. In his autobiography, Black Hawk makes it clear that he considered the counterattack a suicide mission. But the forty massively outnumbered warriors completely routed the miitia, sending them into a disorganized retreat.

What followed was

a

series of small skirmishes and battles with Black Hawk's followers

attempting to escape, and attempting unsuccessfully to surrender.

Black Hawk led warriors and old men, women, and children across what is

now parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, as conditions for them rapidly

deteriorated. Over the long summer many starved or died from illness.

a

series of small skirmishes and battles with Black Hawk's followers

attempting to escape, and attempting unsuccessfully to surrender.

Black Hawk led warriors and old men, women, and children across what is

now parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, as conditions for them rapidly

deteriorated. Over the long summer many starved or died from illness.

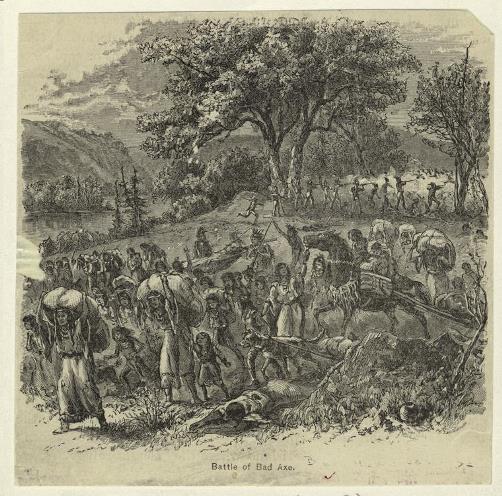

By the first of August, Black Hawk and his party found themselves on the banks of the Mississippi in what is now Wisconsin, just across from the Iowa and Minnesota border. The group was now down to a little over five hundred, and their enemies were closing in on them from all sides. The party split, with a small number of warriors going to the north. The rest of the group, which included most of the women and children, intended to construct rafts to cross the river. But the troops found them first and fired on them. What followed has been called the Bad Axe Massacre. Many of the Sauk were killed in the initial one-sided battle, more were killed while trying to escape across the river, where they were fired upon by the steamboat Warrior. Many who escaped were killed by Sioux, acting on behalf of the U.S. Government.

Black Hawk eluded capture, but was pursued by some of the other Native American leaders, and surrendered by the end of August.

He was turned over to General Street, then to Colonel Zachory Taylor, then down the Mississippi River to Jefferson Barracks. On the steamboat ride down the river he was escorted by a young Lieutenant Jefferson Davis.

Black Hawk was kept as a prisoner of the United States for about a year after the war. Initially he was in chains, but later was treated more respectfully. Andrew Jackson went to St. Louis and talked to the prisoners in April. They were taken on a tour of cities back east, in order to impress upon Black Hawk the strength of the United States and the futility of engaging in war with it. In the fall of 1833 Black Hawk was returned to his home, now in Iowa, and turned over to the custody of Keokuk.